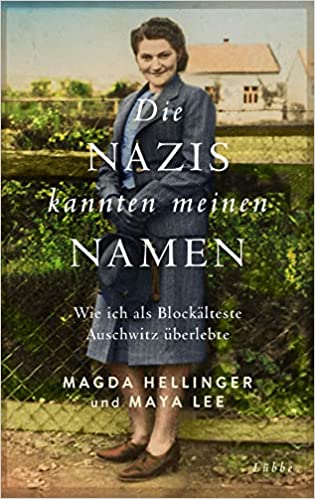

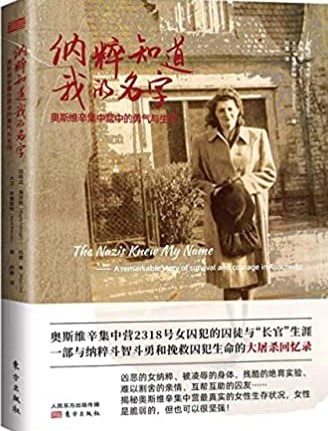

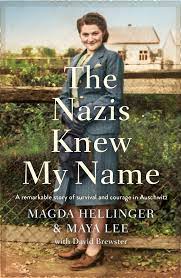

The Brighton Savoy is pleased to introduce you to the first book by our owner and founder Maya Lee called The Nazis Knew My Name – A remarkable story of survival and courage in Auschwitz,

In March 1942, twenty-five-year-old kindergarten teacher Magda Hellinger and nearly a thousand other young Slovakian women were deported to Poland on the second transportation of Jewish people sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The women were told they’d be working at a shoe factory.

At Auschwitz the SS soon discovered that by putting Jewish prisoners in charge of the day-to-day running of the accommodation blocks, camp administration and workforces, they could both reduce the number of guards required and deflect the distrust of the prisoner population away from themselves. Magda was one such prisoner selected for leadership and over three years served in many prisoner leader roles, from room leader, to block leader – at one time in charge of the notorious Experimental Block 10 where reproductive experiments were performed on hundreds of women – and eventually camp leader, responsible for 30,000 women.

She found herself constantly walking a dangerously fine line: using every possible opportunity to save lives while avoiding suspicion by the SS, and risking torture or execution. Through her bold intelligence, sheer audacity, inner strength and shrewd survival instincts, she was able to rise above the horror and cruelty of the camps and build pivotal relationships with the women under her watch, and even some of Auschwitz’s most notorious Nazi senior officers including the Commandant, Josef Kramer.

Based on Magda’s personal account and completed by her daughter Maya’s extensive research, including testimonies from fellow Auschwitz survivors, this awe-inspiring tale offers us incredible insight into human nature, the power of resilience, and the goodness that can shine through even in the most horrific of conditions.

READ AN EXTRACT

The more I had the chance to observe the prominent SS – people like Eduard Wirths, Josef Kramer and Irma Grese – the more I understood that despite their murderous practices, they were still human beings. I don’t say this to excuse their actions in any way, or to suggest that I liked any of these people for even a second. On the contrary, realising that they were human helped me under-stand that they had human needs and vulnerabilities. This created opportunities. People like myself and Vera Fischer – people who had arrived at Auschwitz on the first transports – learned to talk back to the SS if we were careful and chose our times. There was always fear. Any of them could, at any time, have us killed or kill us themselves. But if we maintained respect, avoided ever telling them what to do and acted with the right amount of chutzpah, there were ways we could manipulate them.

There is no better example of this than the way I was able to work with Irma Grese.

After the war, Grese became known as perhaps the most infamous female SS guard. She was young, attractive and earned a reputation for promiscuity and extreme cruelty at the Ravens-brück, Auschwitz–Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. During the so-called Belsen trial in 1945, when charges were heard against Grese, Josef Kramer and forty-three others accused of war crimes at Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, Grese became the centre of much of the media’s attention. They gave her the nickname ‘The Beautiful Beast’. She was only twenty-two years old when she was sentenced to death by hanging. Grese’s reputation continued to grow in the following years, and in many accounts she comes across as a one-dimensional monster. Yet the Grese I knew was also a person. Yes, an evil person capable of terrible sadism, but also a damaged young person who, under-neath everything, was vulnerable and impressionable.

Irma Grese arrived at Camp C on the day after we moved into the sector. When I saw her walk into the camp, I approached her and reported for duty.

‘Lagerführerin Grese. I am your Lagerälteste. We will try to work together. ’Grese was the only SS guard who was permanently based in Camp C. She had an office in the small guardhouse at the gate of the camp, where there was also a guard on duty at all times who kept watch over who was coming and going.

At least once a day she would seek me out to talk to. We often had conversations like those we’d had back at the Brotkammer at the Auschwitz main camp, and it felt like she saw me as a big sister. She would chat to me in the indiscreet way of a young person trying to impress someone older. She sometimes told me about her family: she was one of five children from a regional area of Germany, her father was a farmer and she had lost her mother when she was a young teenager. She told me about her school years in her early teens, during which she had joined the BDM – the Bund Deutscher Mädel, or League of German Girls, a female Nazi youth organisation. She was quite proud of this because the organisation was only open to ‘genuine’ Aryans, and she became very enthusiastic about the ‘mission’ of the Nazis and the ‘dangers’ of race ‘pollution’. As she told me things like this it was almost as if she had forgotten that she was talking to a prisoner, let alone a Jewish prisoner. She told me that her joining the BDM had caused a split in her family, as her father was very religious and conservative and did not believe in Nazism. He had become even more angry when she eventually joined the SS and, after she returned home to visit one time dressed in her full SS uniform, he had not spoken to her again.

She also told me about her career. She had wanted to become a nurse and had worked in the Hohenlychen Sanatorium with Professor Doctor Karl Gebhardt. I had not heard of the profes-sor, but Grese revered him as a ‘saint’ of the Nazi party. After the war it was revealed that Gebhardt was one of the earliest doctors to perform experiments on those the Nazis saw as subhuman, such as the Jews and the Roma. However, Grese didn’t succeed in becoming a nurse, and eventually left the hospital. She worked in a dairy for a short time before volunteering to join the SS, still only eighteen years of age. She told me that she hadn’t known about the concentration camp and that she couldn’t have imagined they would be as bad as they were, but that the Nazis had made working in a camp sound appealing.

Regardless, once she joined the SS she took to the job with great loyalty. She put a lot of effort into wearing her uniform properly and keeping her appearance smart, unlike most of the other guards. And she did what she had to do to stand out and advance herself. By the time she was assigned to Camp C, at just twenty years old, she had been promoted to the rank of SS-Oberscharführerin, the second highest rank available to a female SS officer – something very rare for someone so young.

Occasionally she would also share things she had heard about the Nazis’ plans to win the war. She would tell me gossip about the other SS women, none of whom she was friendly with.

I thought sometimes that perhaps this was why she treated me as a big sister and not as a prisoner. I was the only person she could talk to. While she would appear almost familiar with me, she soon earned a reputation for brutality – and I saw this side of her too. During roll call one day I was standing in front of Block 2. Suddenly two runners came up to me with four very distressed women whose breasts had been split open. It was a terrible sight, the poor women crying out in pain, their breasts bleeding badly. I asked them what happened and who did this to them, but they were too frightened to reply.

One of the runners said, ‘This one told me that LagerführerinGrese struck them with her whip.’

I told the Läuferinnen to take the women to the Revier.

‘Tell Dr Perl I sent you and that she should try her best to help these poor women.’

I then found Grese and, making sure no one else could hear me, said, ‘What did you do to those poor women? They are in great pain. Their wounds will likely become infected and they will die. Shame on you.’

She lifted her whip.

‘I dare you to strike me too,’ I said. ‘I know you like to see blood. Ich bin beleidigt.’ ‘I’m offended.’

I turned and walked away.

Later, to my astonishment, Grese came to me and said, ‘Vergib mir.’ ‘Forgive me.’

From then on she rarely showed her sadistic side if I was around, but sadly that side did come out many times. She wanted power and all the luxuries that she could have with it, and that meant outshining all the other female SS in both looks and brutality. There were many other reports of her using her whip or her pistol, or having groups of prisoners ‘make sport’ during roll call. It was always mysterious to me that she would show me so much respect yet could be so heartless and cruel to so many others, one minute talking to me as a friend and the next minute being a sadistic devil.

Review 4.5 out of 5 stars

‘This is an excellent read for those interested in a more detailed history of the Holocaust. The rare and fascinating personal accounts of infamous SS guards and personnel help to make The Nazis Knew My Name unputdownable, while Magda’s enduring choice to save who she could will hopefully inspire kindness and selflessness in another generation’ Reviewed by Vanessa elle.

Television Media

Interviews

Online Media

Time.com – Why i am telling my mum’s story.

New York Post 4th September 2021 These are the must-have books for fall 2021

The Australian Jewish News 17th September 2021. The Legacy of 2318

Good Readings Magazine Book Extract

Forward.com – Negotiating between heroism and colloration

Radio

A Literary Lunch: Maya Lee On Nightlife with Philip Clark

Reviews

Kirkus reviews – A poignantly illuminating Holocaust memoir.

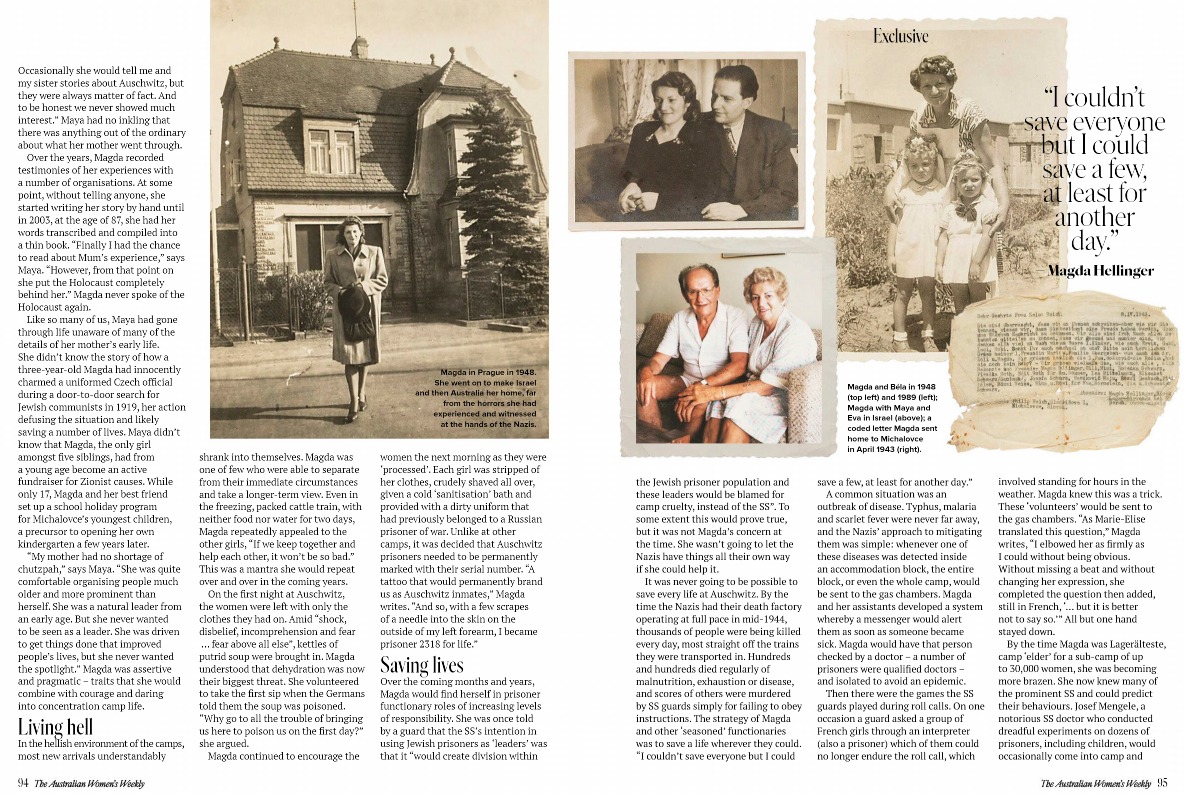

Australian Womans Weekly September 2021

Buy English version

Buy English version