An article by Des Lee’s good friend Tamas Karpati that appeared in the Hungarian Publication Nemzeti Sport on the 22nd August 2020. (Translated into English by A.K Karpati.)

He played football against Öcsi Puskás and guarded Leo Horn’s legendary whistle. An adventurous journey from Vértes to Melbourne. Remembering Dezső Lévi.

HE HAD NOTHING TO LOSE

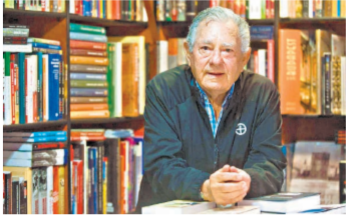

“I had to mark Puskás, you can imagine…” reminisces Des Lee (hereon onwards Dezső, as he was born as Dezső Lévi in August of 1933, in Vértes near Debrecen) in the Australian summer, standing in the hot sand in front of his seaside hotel, looking for a tiny patch of shade by the century-old, colourfully painted beach cabins.

“I served in the army in Eger in the early ‘50s, and Honvéd came to play an exhibition game. My coach must have had something against me, as he came up with the tight marking tactic against Öcsi. In all honesty, if he had walked past me on the street after the game, I am not sure I would have recognised him. I did not get to see much of his face during the game, but rather his back much more often. The next time we met was about three decades thereafter, here, in Melbourne. Between a round of ulti and some homemade stew he kept teasing me, that ever since that game he has been trying to figure out which centre-back my skills reminded him of the most: Lóránt at the peak of his strength, Santamaría or Bellini.”

I jumped ahead a little, as I still owe the story of how we got acquainted. Actually, this was also due to playing ulti, when Gyuri Korda was kind enough to invite me to his house on the shore of Lake Velence, at the time when Dezső and his wife, Maya, were staying there as guests.

At the card table it became clear that Dezső is interested in everything that connects to the old homeland, especially if that something is sports or culture related. He said the flight to Pest is a little expensive, so he “cut costs” by inviting his favourites for a personal performance or story telling evening to the Brighton Savoy, the hotel he built himself: Laci Papp, the already mentioned Puskás, “Gyurika” Kárpáti, Hofi, the little Kabos, the 100-member Gypsy Band, Kata Csongrádi, Marika Németh, Judit Hernádi, Bilicsi, and also the entire Hungarian tennis and water polo national teams have all been his guests.

While enjoying the Hungarian flavours served by Klárika, I also learned that Dezső is a fan of Hungarian cuisine not only as a guest but also as its creator. The next day we had lunch in Kéhli Restaurant in Óbuda, once the favourite eatery of Gyula Krúdy. Already the first course, the “peasant-platter” fascinated my guests, not to mention the second: hot pot with marrow in a bone, served traditionally in small red pots that visibly stood the test of time, at tables covered in chequered cloths. Following the meal – resembling Marco Ferreri’s classic, “The Big Feast” – the “dessert” was a tour of my HungarIcons art collection. Neither at home nor abroad did I experience at exhibitions that the relics of famous Hungarians – Kodály and Bartók, Balczó and Jutka Polgár, Jancsó and Makk, Barcsay and Vasarely – reimagined by contemporary artists, would have made such an amazing impression on any visitor. Dezső, from the distance of six decades and sixteen thousand kilometres, could stand for minutes, battling emotions, in front of a pair of glasses, a walking cane, football boots or a swim cap. After having inspected the collection down to the last piece, he simply said the following: “If you ever happen to come by my place, I’ll give you something”. I politely thanked him, but there was no real danger of me starting to explore Australia anytime soon, since in the past six and a half decades I did not “happen to be” in that part of the world.

Two months later a large black SUV – with the license plate LEE 007 – stopped outside the terrace of Rococo, one of St Kilda Beach’s iconic cafes. That’s all for the James Bond analogy, no further crime elements in the story. Dezső jumped out of the car with the flexibility of a well maintained eighty-something year old, and we greeted each other as old friends, despite the fact that we had only met on two or three occasions prior to this. My life in the meantime unfolded in such way that for a few years – due to my son’s relocation – I had the good fortune of spending the Hungarian winters in the Australian summers. Dezső, as proud host, was guiding me (this was the year 5 B.C., ie. “Before Covid”) around the sights and landmarks of the most liveable city on the planet. Memorials, arboretums, the Yarra embankment (like our own Duna-korzó), the Melbourne Victory stadium – where the home team’s anthem is Stand By Me –, little butcher shops with home flavours, the Olympic statue park – where the Puskás statue was to be unveiled two years thereafter –, the terrace of Esplanade where a certain musical formation called AC/DC once gave its first concert for a mere 15 people. Finally, we ended up in Brighton, in my host’s gorgeous home, equipped with a pool and a tennis court, where hanging on the walls you can equally find art from aboriginal masters as well as landscapes from reputable Hungarian artists.

Dezső kept the real surprise for after dinner. From the bottom of a safe he pulled out a small container out of which emerged a whistle. “It was last used by Leo Horn” – he added with some emphasis. “You don’t say…” – I was overwhelmed. “I do! The whistle of 6:3. I got it from Öcsi Puskás. And now I give it to you with love, I think the best place for it will be among the HungarIcons.”

Of course, I could not have said it better myself, but a few minor details need clarification. How did the butcher boy from Vértes end up as a hotel-owner in Melbourne? How did this sport historical object make its way first to Puskás, then to Dezső? And finally, how did Zoltán Bohus, one of the most famous glass sculptors in the world, build a beautiful green glass mausoleum around it?

The first question above has an obvious answer: “I had nothing to lose.” This is the title of Dezső’s autobiography, published multiple times in Australia, which also reached our readers at home in the form of a Hungarian translation published in 2016. He also spoke about his adventurous life in front of cameras to Holocaust survivors, at an event organised by an institute established by Steven Spielberg.

“My story starts in Vértes, a small village in East Hungary – so the preface reads – where we lived a happy, peaceful and safe life as one of the most prominent families of the county. We survived the murderous Nazis and life came back again, only for us to be treated as guilty again, this time by the regime created by the Communists. Antisemitism popped up again in the country, following the revolution in 1956 against Soviet oppression (…) we decided to leave in the hope of a more peaceful life.”

Typical Jewish fate? Typical Hungarian fate? Typical 20th century destiny? What is atypical is Dezső’s personality. A strange mix of power and selflessness, hedonism and full empathy, a full heart and a strong mind.

He learned it all from Tata, his grandfather who was the proud parent of twenty-one children, with whom they were inseparable day and night. He learned to herd horses, cut ice on the lake, lay bricks, debone meat and harvest tobacco. Then, just like the youngest child in all fairy tales, he left to try his luck. The young adolescent really did need all of grandpa’s advice and life wisdom, to survive the ghetto and the concentration camp, at the time when the family emigrated, and in a series of other, challenging life situations.

When Puskás – as the coach of the Australian championship winning team – gave in to siren sounds calling from home, and in the early ‘90s moved back with his family to Hungary, a difficult and painful farewell preceded his trip. He had to say goodbye to one of his best mates, in style, with a strong friendly hug. He pulled something out of his pocket, but only showed it after he finished what he wanted to say.

“I do not get attached to objects, but for almost three decades this was my good luck charm, I took it everywhere and guarded it as one of the nicest memories of my life. I cannot give you anything else, that could possibly reciprocate the brotherly love I got from you, from both of you, over the past years. A whistle. I asked Leo Horn for it on 25th November 1953, right after the game. He was refereeing the 6:3 with it.”

The whistle of Horn, the one-time Dutch partisan, had a few “farewell performances”. In Canberra and Melbourne Dezső blew it as guest of honour, at a theatre premiere in Veszprém Károly Eperjes blew it and created a small panic in the room, while the New Hidegkuti Nándor Stadium was officially opened, following the prime minister’s speech, to the sound of this very whistle. After these events I gave it to Zoltán Bohus, the doyen of Hungarian glass artists, at the time not knowing that this would be his last piece of art ever. Bohus expresses the most, by using the least, “he sneaks lyrical thoughts into pure geometry, with the help of the trapped light he installs poetry into logical shapes”. A wonderful piece was born, last year when Dezső came to visit he stroked it emotionally. Now we know that he came to say goodbye. To friends, to memories. To the grandiose willow sculpture created by Imre Varga in the garden of the Synagogue in Dohány utca, which would not stand there without Dezső’s generosity.

He told me in a sad voice that once – well over 70 already – they cycled around Balaton with Maya, just like earlier, when they toured from Passau to Pest, Saigon to Hanoi, and even explored all of New Caledonia on bicycles. Today, the “iron-stallion” is a distant memory. What’s more, the weekly two tennis sessions with Gyuri Szegő, that lasted for fifty years, are also over.

Gyuri, five years Dezső’s senior, had an equally improbable life, enough to mention simply that he successfully completed medical degrees in three different countries in three different languages. His literary books and professional publications made his name known worldwide. Over the last five years I had the distinct honour of joining the two forever friends on their walks every Tuesday and Thursday morning in the fabulous Caulfield Park, listening to their light banter. As if the Muppet Show came to life, with the two adorable, forever critics quarrelling in the lodge, who on top of that mixed “Hunglish” with Jiddish, in fact, in my opinion they spoke stylishly in 6:3: six Hungarian words followed by three English ones. Gyuri, the psychiatrist, would then point to Dezső behind his back, with a wise smile and simply say: “And he is MY psychiatrist”. In the evenings they would meet again, mostly at the house of Zsuzsi Vati where 10-15 Hungarian families regularly came together to quote from Toldi, recite Ady and Pilinszky, or read Örkény and Faludy – to cherish whatever there is left from their homeland.

One day before returning home from Melbourne, on the 13th of March 2020, I wanted to say bye to Dezső. He was immersed in his afternoon nap so peacefully that I did not have the heart to wake him. Then I found out from the Facebook post of his children, Jenny and Michael, that their father made a decision: he would no longer submit to life saving medical treatment. He did not want to die, simply did not want to live (like that). A few days ago, the news arrived: “On Thursday the 13th of August 2020, our Father passed away peacefully in his sleep.”

Dezső Lévi would have turned 87 on Sunday, 23rd of August 2020.

Alav ha-shalom. May he rest in peace.

The Article as it appeared in Nemzeto Sports Lévi Dezső_NemzetiSport

Footnote

On 25 November 1953, an international football match was played between Hungary—then the world’s number one ranked team, the Olympic champions and on a run of 24 unbeaten games, and England, became know as the match of the century, with Hungary defeating England 6 – 3 goals.